I have the great honor and privilege to speak to the Association of Independent Music Publishers (AIMP) on Wednesday, September 25, 2013 at ASCAP in Nashville. Here is the announcement and details about my presentation. Surprisingly (to me) there are two words in CAPS that I never see used in conjunction with me: SOLD OUT. Fortunately this refers to the fact that there is no more room for the luncheon at ASCAP where I am speaking and NOT that I have SOLD OUT (my principles). Or so I am going to assume.

__________________________________________________________________________________

My work as a consultant in copyright and intellectual property (IP) matters is always fun and original as very crazy things can occur when we creators create. I get brought into some of the events surrounding potential and actual problems. I have been and continue to be witness to brilliant decision making, as well average and poor decision making when it comes to music, IP law and money. People do things that will make them profits and prosperous. Some do average, ho-0hum expected things, and yet others make bad decisions that will be negative financially for more than 100 years. (Copyrights might outlive many glaciers at the northern and southern ends of our planet. When a 30 year-old gives up part or her copyright, it is a decision that could last for 130 years. Assuming she will live 60 more years, her copyright will last 130 more years: 60 years alive + 70 years after her death. And I expect that every twenty years, copyright will be extended another twenty years – the 130 year decision might become a 200 year decision.)

We have been and continue to be surrounded by IP – train and car horns blast their metal music made from metal objects, adverts are seen and heard mostly with music or sounds, radio sometimes play music (in those few radio stations when radio is not presenting the sounds of more adverts and humans speaking to and at each other, i.e., “talk radio”), the Internet, music on the Internet, televised and transmitted images (often with sounds) from mobile devices, large devices, billboards, etc.

We absorb and reflect a lot of the sounds, sights, ideas and attitudes we perceive. We have to copy some of it as it is important that we use UNORIGINAL words in our speech, writings and music, and UNORIGINAL melodies, chords, rhythms, sounds and loudnesses in our music. (With respect to music, I am referring to UNORIGINAL, individual (or very brief-lasting) musical components. ORIGINAL expression usually consists of UNORIGINAL elements strung together in ORIGINAL ways.)

Problems that can happen include:

1) What we create sounds like something else, something already created.

2) What we create looks like something else, something already created.

3) What we create sounds and looks like something else, something already created.

And some might say, “So What?” And in response one might say, “So What? You stole my song, that’s ‘So What.’ Your success is due to infringing my copyright. You’re only successful because of my creativity, my ideas, my expression, my copyright. (My my my….my.) I’ll see you in court!” (Oh, but it is never that simple.)

Two more things before I get to fair use.

1. We STEAL (copy) ACCIDENTALLY. Let’s be kinder – let’s say it this way. We inadvertently copy from other sources. How can we NOT copy from other sources when we are bombarded by external stimuli?

2. We STEAL (copy) on purpose. We INTEND to STEAL (copy) and we do. We copy because we like the sound of some preexisting sound, or the sound and effectiveness of some preexisting chord, chords, phrase of a melody, phrases of text or lyrics, individual words, certain instruments (a Coke bottle has been in the music copyright infringement news lately – that ubiquitous Blurred Lines by Robin Thicke, and its imitation of Marvin Gaye’s Got To Give It Up), combinations of instruments, sounds, combinations of sounds, etc.

There is a part of the Copyright Law that acknowledges and enunciates that we can make use of an original work of authorship – “original work of authorship” that is NOT our work, and WITHOUT permission – if we have a good reason for doing so. This part of the Copyright Law is Section 107. It is entitled, “Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use:”

“§ 107. “Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use.“

Copying someone else’s expression is allowed. Perhaps it is more accurate to state it this way: Copying someone else’s expression is possible. Is permissible. Can happen. Can happen without negative consequences. (Fair use can mean that one has the right to hire expensive attorneys to fight back against a plaintiff’s assertion that you have infringed her copyright. The “without negative consequences” is initially a theory – it often takes time, money, attorneys and experts to negate the “negative consequences.”)

As to why and how one can use someone else’s creations – their original work of authorship without their permission – the authors of the Copyright Law might have been careful and diligent in listing SOME of the reasons why it would be permissible to not seek permission:

“…for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research…”

“The fair use of a copyrighted work…is NOT an infringement of copyright.” (I capitalized “NOT” in that sentence from Section 107 .)

__________________________________________________________________________________

I will delve into fair use today as well as the other related subject below. My flow today will likely go this way:

1. The definition of “original”

2. With respect to music and copyright, examples of Bad Lawyering/Bad Lawyers in Bad Practice (there is not a kinder way of expressing this.)

3. What is fair use? Examples of fair use – copying music only, words only, words and music.

4. What is “co-authorsip?” What is a “joint work?” The assessment of each writer’s expression in a joint work.

5. The Worst Music Publishing Mistake Ever Made By Famous, Wealthy Musicians

6. My most recent work for a plaintiff

7. “…As the world turns….As copyright becomes irrelevant…”

__________________________________________________________________________________

I will play and discuss music from these composers/creators/authors/artists. (As you might guess, many of these will be short excerpts.)

Aerosmith

Atomic Kitten

B. S. G.

Baby Game

Burt Bacharach

Baha Men

Barrio Boyzz

Bela Bartok

Beatles

Bon Jovi

Asha Bhosle & Kishore Kumar

Jimmy Boyd

Garth Brooks

Brooks & Dunn

Circle Of Success

LL Cool J

Jonathan Coulton

Cream

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Crime Boss

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young

Culture Club

Joe Diffie

Hilary Duff

Dr. Dre

Bob Dylan

Eminem

Fatback Band

Fifty Cent

Flintstones

The Game

George Gershwin

Isaac Hayes

Jimi Hendrix

Faith Hill

Buddy Holly

Hootie & The Blowfish

Mary Hopkin

Marques Houston

Jefferson Airplane

Elton John

George Jones

Montell Jordan

Wiz Khalifa

King Crimson

Krayzie Bone

k.d. lang

Lil Malcolm

Little River Band

Lootenant

M.I.A.

Madrugada

Gustav Mahler

Mary Martin

Mistah F.A.B.

Sir Mix-A-Lot

Mystikal

Nirvana

The Orioles

Outkast

Pearl Jam

Scoob Rock

Snoop Dogg (Snoop Lion)

Sonic Dream Collective

Britney Spears

Naomi Striemer

Supertramp

James Taylor

Wham!

Lil iROCC Williams

Bill Withers

Youngbloods

9 Milli Major

__________________________________________________________________________________

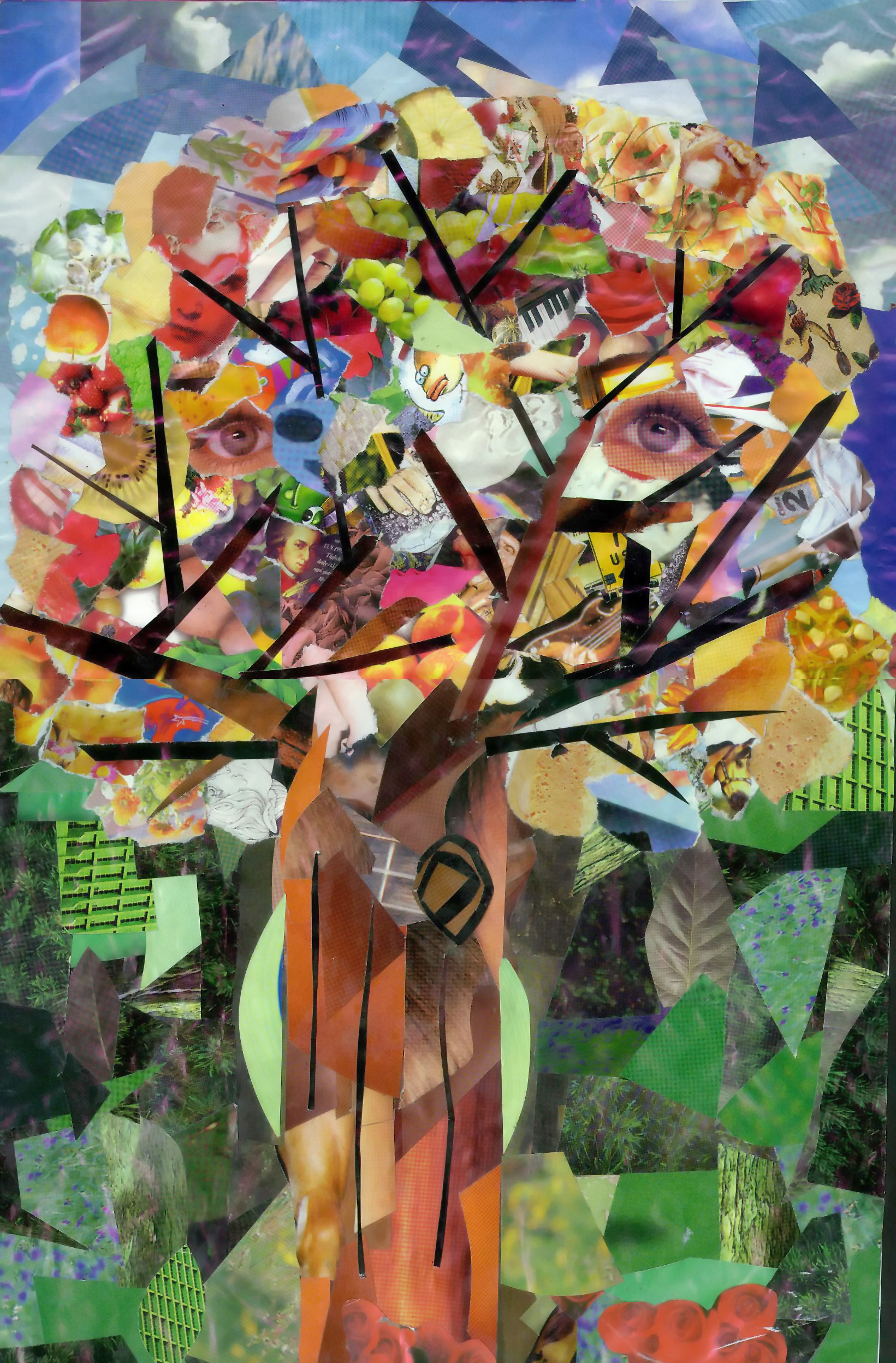

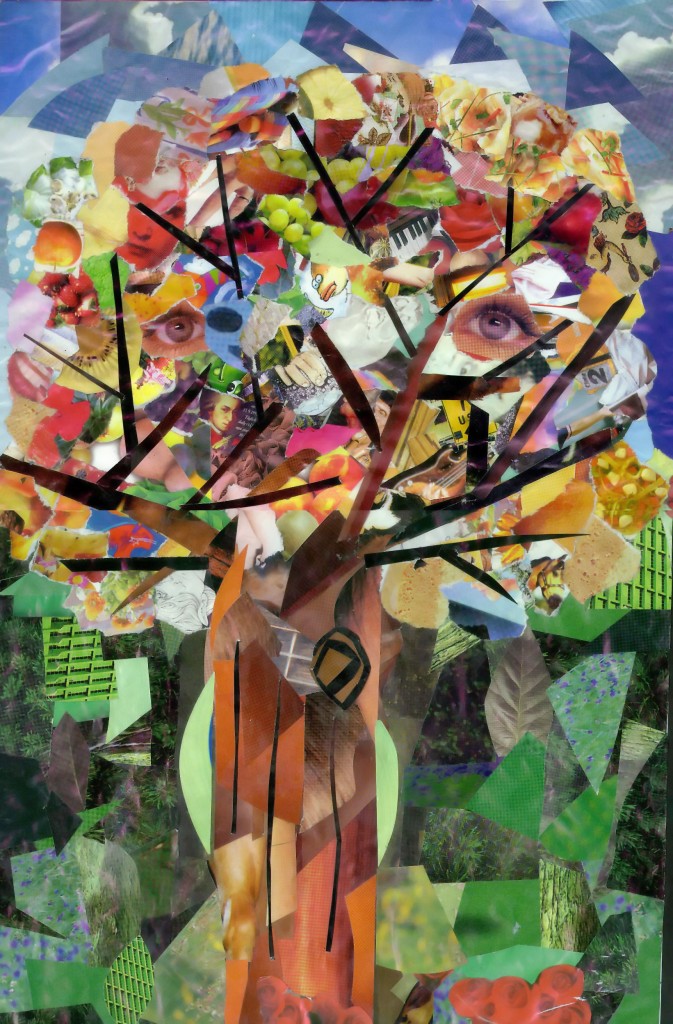

Happy Autumn! I hope you enjoy the cover photograph.

Wishing everyone a surprising and happy Wednesday.

__________________________________________________________________________________